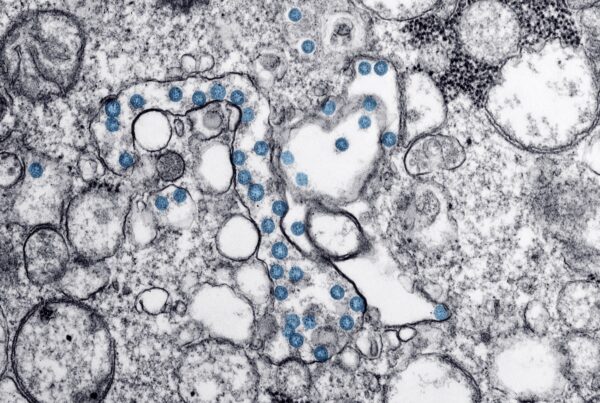

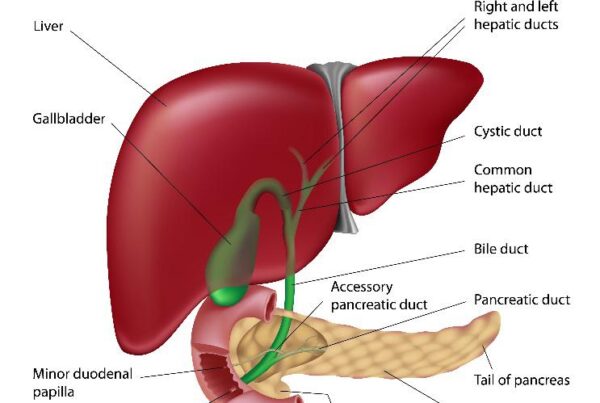

Coronavirus and the GI system: What does the evidence tell us?

August 26, 2020

Coronavirus and the GI system: What does the evidence tell us?

The coronavirus continues to have an enormous impact on the way we live. Over the…

Recent Comments